Writing in The Irish Times last week, the economist Brendan Kearney, formerly assistant director of Teagasc, argued that there is no prospect of a cattle price emerging high enough to place the Irish suckler herd in the black.

The fundamental economics are unfavourable, especially for small-scale producers, and he does not see how this can be expected to change. Beef demand in Europe is sluggish and the drift in consumer sentiment away from meat consumption is a train that has left the station.

This is a bleak outlook and owes nothing to any new measures which might emerge from efforts to tackle climate change

Incomes for beef producers are supported by non-farm work and by the Basic Payment Scheme, but even with these supports Kearney argues that long-term decline in the numbers engaged in the beef sector is inevitable.

The Government does not set cattle prices and the EU is not going to offer a new regime of headage payments or price supports.

This is a bleak outlook and owes nothing to any new measures which might emerge from efforts to tackle climate change. It owes nothing either to the Mercosur deal, which caused so much agitation a few months back.

The protesters who disrupted Dublin traffic last week enjoy a measure of public sympathy and have suffered a genuine drop in income from weak prices.

For every dairy farm in Ireland, there are roughly five beef farms

Price is the problem all right, but it is not a new problem: beef production has become less viable in recent years, but it was never particularly profitable even in better times.

If prices adequate to deliver sustainability to most suckler farmers are not likely to emerge, the consequences for the sustainability of rural communities are serious.

For every dairy farm in Ireland, there are roughly five beef farms, a total of 90,000, many of them part-time. Only about one quarter of these cover production costs. For the remainder, Kearney concludes: “To put it bluntly, there is no conceivable increase in beef prices, which will yield an increase in income which will materially improve living standards on such farms.”

This policy may not make much sense for the UK’s negotiating position in the trade talks with the EU-27

Aside from the weakness in demand for meat, driven by consumers deciding on a roll-your-own climate policy, Brexit could see access to the British market curtailed as soon as January 2021 if the Conservatives win the election and push ahead with their declared intention to end the transition period at the earliest available date.

This policy may not make much sense for the UK’s negotiating position in the trade talks with the EU-27 but Boris Johnson has made the commitment. It would mean at worst and in just over a year from now, tariffs on exports to the UK, as well as non-tariff barriers.

The optimists will be hoping that Johnson is not to be believed and that he will extend transition, but that postpones the move to restrictions on access for at most two more years.

Even if the beef farmers succeed in securing reforms to factory prices, the amount of any income improvement is not likely to be material

Such an outcome would also see restricted access for dairy products, affecting the most profitable sector of Irish farming and the one where output has been rising strongly since the abolition of quotas in 2015. But the fundamental economics are better for dairy and there are alternative markets to develop.

Even if the beef farmers succeed in securing reforms to factory prices, the amount of any income improvement is not likely to be material. The problem is that the small-scale beef enterprise will not be rescued by any conceivable enhancement to the division of the spoils between the factories and the farmers.

Long-term issue

The long-term issue is the ultimate market value of the meat produced from the sector more than the split between farmers and processors, however unfair that split is perceived.

The Government’s climate advisory council has recommended, as does Brendan Kearney, that farmers should consider alternatives, including forestry and there is scope for a fresh look at forestry incentives and the maintenance of support payments through any adjustment phase.

The majority of the 99,400 derive at least some of their income from suckler beef

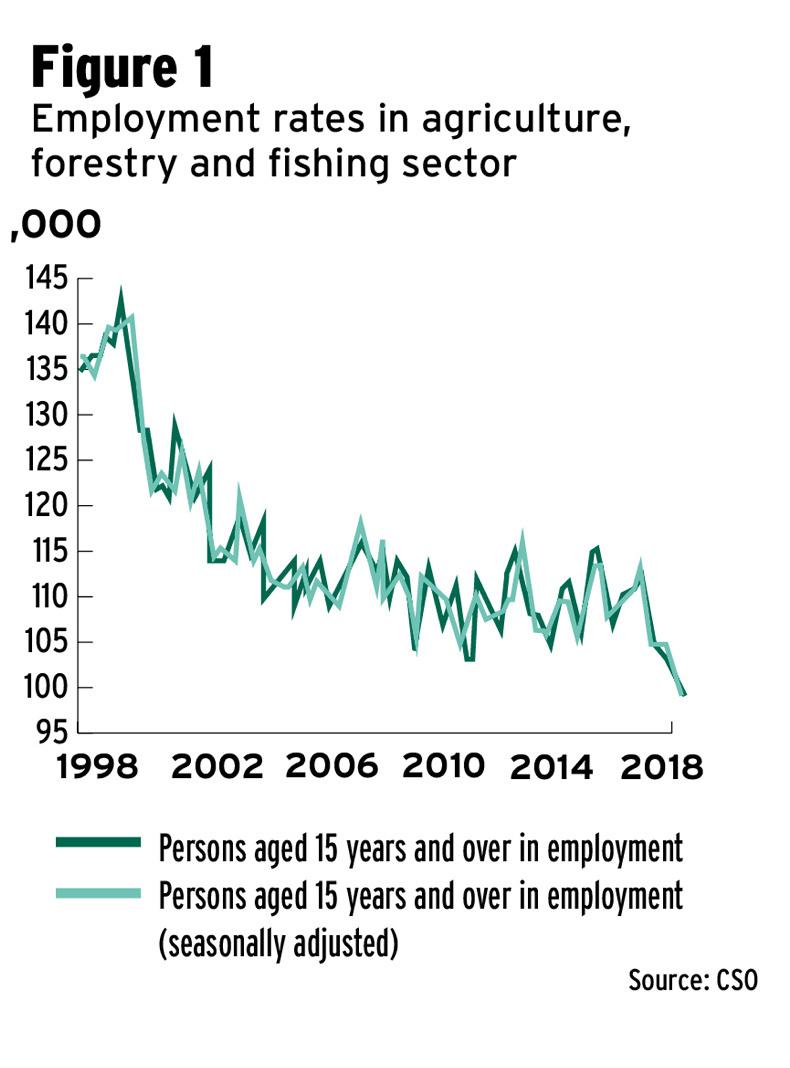

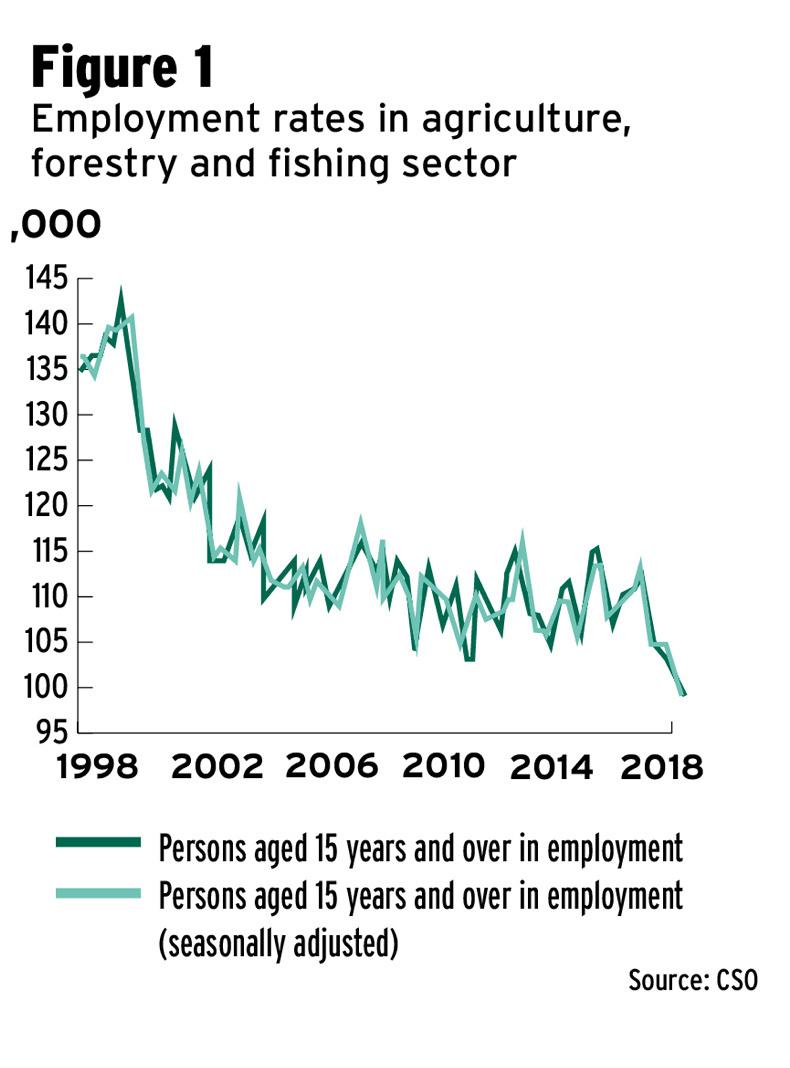

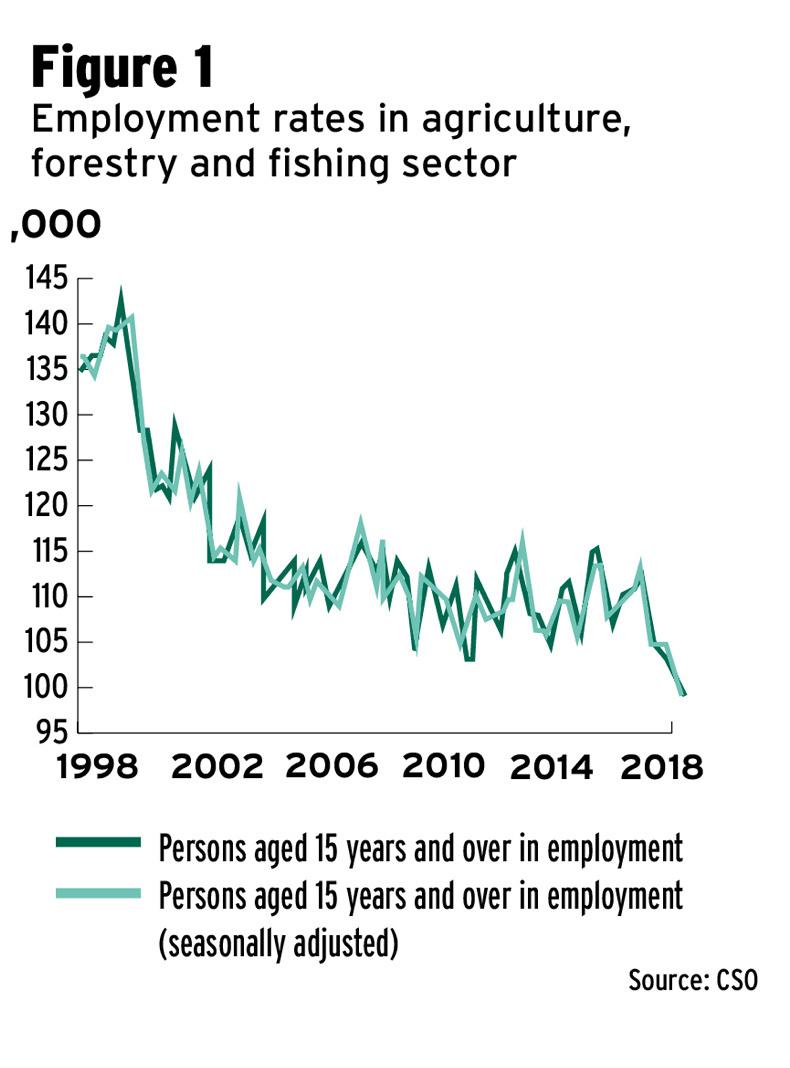

Figure 1 shows the steady decline in employment for the sector called agriculture, forestry and fishing from the Central Statistics Office.

There are now just 99,400 employed in primary production, falling this century at about 2,000 per annum, out of a national figure at work of over 2.3m.

The downward trend is unmistakable and has accelerated recently with the broader economic recovery. The majority of the 99,400 derive at least some of their income from suckler beef.

The political parties will be facing the electorate shortly and need to consider the design of policies which will ease the transition for those affected by the further contraction, which Brendan Kearney sees as inevitable.

Read more

Does rising global beef price remove Mercosur threat?

Farmer Writes: it's a frustrating time to be a farmer

Writing in The Irish Times last week, the economist Brendan Kearney, formerly assistant director of Teagasc, argued that there is no prospect of a cattle price emerging high enough to place the Irish suckler herd in the black.

The fundamental economics are unfavourable, especially for small-scale producers, and he does not see how this can be expected to change. Beef demand in Europe is sluggish and the drift in consumer sentiment away from meat consumption is a train that has left the station.

This is a bleak outlook and owes nothing to any new measures which might emerge from efforts to tackle climate change

Incomes for beef producers are supported by non-farm work and by the Basic Payment Scheme, but even with these supports Kearney argues that long-term decline in the numbers engaged in the beef sector is inevitable.

The Government does not set cattle prices and the EU is not going to offer a new regime of headage payments or price supports.

This is a bleak outlook and owes nothing to any new measures which might emerge from efforts to tackle climate change. It owes nothing either to the Mercosur deal, which caused so much agitation a few months back.

The protesters who disrupted Dublin traffic last week enjoy a measure of public sympathy and have suffered a genuine drop in income from weak prices.

For every dairy farm in Ireland, there are roughly five beef farms

Price is the problem all right, but it is not a new problem: beef production has become less viable in recent years, but it was never particularly profitable even in better times.

If prices adequate to deliver sustainability to most suckler farmers are not likely to emerge, the consequences for the sustainability of rural communities are serious.

For every dairy farm in Ireland, there are roughly five beef farms, a total of 90,000, many of them part-time. Only about one quarter of these cover production costs. For the remainder, Kearney concludes: “To put it bluntly, there is no conceivable increase in beef prices, which will yield an increase in income which will materially improve living standards on such farms.”

This policy may not make much sense for the UK’s negotiating position in the trade talks with the EU-27

Aside from the weakness in demand for meat, driven by consumers deciding on a roll-your-own climate policy, Brexit could see access to the British market curtailed as soon as January 2021 if the Conservatives win the election and push ahead with their declared intention to end the transition period at the earliest available date.

This policy may not make much sense for the UK’s negotiating position in the trade talks with the EU-27 but Boris Johnson has made the commitment. It would mean at worst and in just over a year from now, tariffs on exports to the UK, as well as non-tariff barriers.

The optimists will be hoping that Johnson is not to be believed and that he will extend transition, but that postpones the move to restrictions on access for at most two more years.

Even if the beef farmers succeed in securing reforms to factory prices, the amount of any income improvement is not likely to be material

Such an outcome would also see restricted access for dairy products, affecting the most profitable sector of Irish farming and the one where output has been rising strongly since the abolition of quotas in 2015. But the fundamental economics are better for dairy and there are alternative markets to develop.

Even if the beef farmers succeed in securing reforms to factory prices, the amount of any income improvement is not likely to be material. The problem is that the small-scale beef enterprise will not be rescued by any conceivable enhancement to the division of the spoils between the factories and the farmers.

Long-term issue

The long-term issue is the ultimate market value of the meat produced from the sector more than the split between farmers and processors, however unfair that split is perceived.

The Government’s climate advisory council has recommended, as does Brendan Kearney, that farmers should consider alternatives, including forestry and there is scope for a fresh look at forestry incentives and the maintenance of support payments through any adjustment phase.

The majority of the 99,400 derive at least some of their income from suckler beef

Figure 1 shows the steady decline in employment for the sector called agriculture, forestry and fishing from the Central Statistics Office.

There are now just 99,400 employed in primary production, falling this century at about 2,000 per annum, out of a national figure at work of over 2.3m.

The downward trend is unmistakable and has accelerated recently with the broader economic recovery. The majority of the 99,400 derive at least some of their income from suckler beef.

The political parties will be facing the electorate shortly and need to consider the design of policies which will ease the transition for those affected by the further contraction, which Brendan Kearney sees as inevitable.

Read more

Does rising global beef price remove Mercosur threat?

Farmer Writes: it's a frustrating time to be a farmer

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: