From a farmer’s perspective, the timing of the EU-Mercosur deal couldn’t be worse. The announcement that the Mercosur bloc of South American countries has secured access for 99,000t of beef at a reduced tariff rate into the EU, plus a total elimination of tariffs on 47,000t Hilton quota, comes as farmers struggle to deal with a collapse in beef price across the EU.

There are two factors at play. First is a slump in demand for beef, reflecting the extent to which many consumers see eating less beef as a step towards doing their bit for climate change. Second is the ongoing market disruption being caused by the threat of a no-deal Brexit.

The move by the European Commission to put forward an agreement with Mercosur has generated real anger among EU beef farmers, and nowhere more so than in Ireland, where farmers feel this is another attempt to wind down the national suckler herd.

So does a Mercosur trade deal spell the end of the sucker cow? It certainly has the potential to but as Minister for Agriculture Michael Creed outlines, the political agreement announced last week has a lot of hurdles still to jump.

Our specialist team analyses the agreement and details the time lines this week. Ratifying the deal will be a slow process. European Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan indicates that it could be 2028 before it is operational – if approved. In this sense, the threat is more distant and should not distract from the challenge of Brexit. If Brexit goes wrong, we will not have to worry about of increased volumes of South American beef in 2028.

Despite some confusion, no EU member state can unilaterally veto the Mercosur deal.

As Phelim O’Neill, the proposed agreement must be ratified by both the Trade Policy Committee (TPC), made up of EU trade Ministers, and the European Parliament. Within the TPC, a qualified majority is required consisting of 55% of member states representing 65% of the population. Minister Creed has committed to frustrate the deal by trying to build a blocking alliance within the TPC. It will be difficult in the absence of French support.

The deal may well face a bigger hurdle in the European Parliament, which, in the wake of recent elections, now has a much greener tilt.

The failure to allocate a specific product quota within the tariff rate quota (TRQ) is a real concern. It allows the Mercosur bloc to cherry-pick steaking cuts into the EU

Given the obvious policy divergence in relation to environmental standards, it will be interesting to see if green MEPs are prepared to show their colours in preventing the Commission effectively moving to outsource their climate responsibilities.

Additionally, perhaps the biggest threat to the agreement reaching completion may be Mercosur itself. The coalition has always proved highly volatile with changes to the political leadership within the trading bloc having derailed previous negotiations.

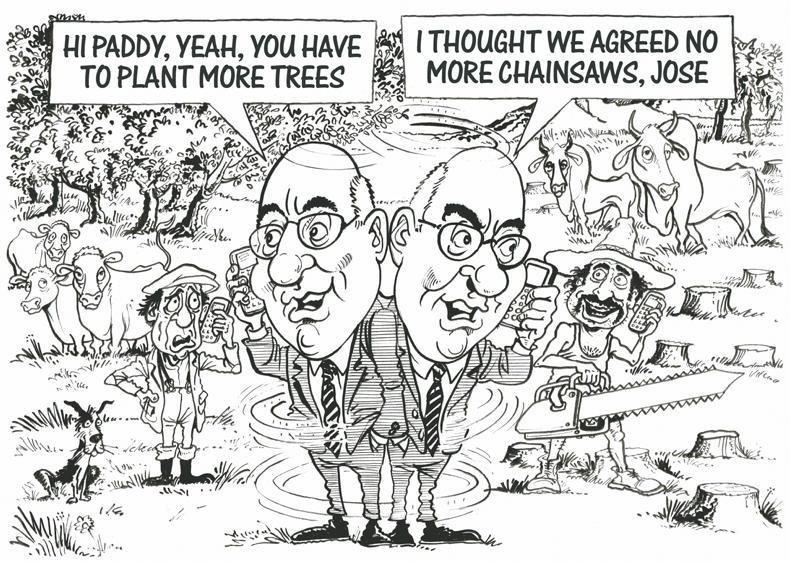

Commissioner Hogan is unequivocal in that if climate commitments – particularly in relation to deforestation – are not implemented, then the deal will be scrapped. With Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro having traditionally leaned more towards Trump-like climate policies, the environmental conditions attached to the agreement will require a transformation in Brazil where deforestation is currently running at record levels.

Assuming all hurdles are jumped and a deal is ratified, Commissioner Hogan has left the EU with no wiggle room regarding standards. In a meeting with the Irish Farmers Journal, he stated that the South American countries will have to comply 100% with EU standards on farms supplying the EU market. This represents a significant change from the past, when Brazilian beef could enter the EU from farms where standards did not mirror those in the EU.

Given Brazil’s inability to meet equivalent standards and the EU’s failure to adequately monitor standards, the IFA is right to be suspicious of such commitments from Hogan.

The failure to allocate a specific product quota within the tariff rate quota (TRQ) is a real concern. It allows the Mercosur bloc to cherry-pick steaking cuts into the EU, allowing the potential to cause huge market disturbance. However, Commissioner Hogan argues that the introduction of a safeguard mechanism that allows for a two-year suspension of trade where evidence of market disruption can be identified provides the necessary protection.

Key to protecting the EU beef and poultry market in the event of any deal will be to ensure climate, production and welfare standards are enforced. Both farm organisations and MEPs should demand that before any deal can be ratified, an independent competent authority should be appointed to ensure that all measures contained within the agreement relating to standards, animal welfare and environmental controls are fully implemented, and that safeguards are triggered when required.

We should remember that in the past, when Brazil was forced to meet EU standards, the added costs saw their appetite to supply the EU dwindle.

There is no upside in the Mercosur agreement for the beef and poultry sectors. However, it doesn’t mean that it is time to shut the door on our suckler sector. Any deal will take up to a decade to come into full force so there is no need for immediate panic or to be distracted from more immediate Brexit issues.

Regardless of what happens in Mercosur, the need to develop a coherent strategy for our suckler herd is clear.

Hogan insists that tools are in place under the CAP to protect the financial viability of suckler beef production in Ireland. However, this will require Minister Creed and farm organisations to debate the thorny issue of top slicing payments to establish a fund to protect vulnerable sectors.

The willingness within the European Commission to establish a new REPS scheme and couple supports for sucker cows shows the scope that exists to provide financial support.

These supports must be in place well in advance of any Mercosur deal.

Moorepark open day: huge turnout reflective of a sector that is driving ahead

The turnout in Moorepark on Wednesday was testament to a sector that is driving ahead in more ways than one. The enthusiasm was palpable from dairy farmers who have been milking cows for over 30 years, other farmers considering milking cows and a large cross-section of the service industry.

Like any sector leaving a margin, the spin-off into rural Ireland is real and that’s what creates the buzz.

It all hinges on dairy farmers managing grass properly and using highly fertile genetics – the message has been consistent for a good number of years at similar days. There are of course challenges but none insurmountable once managed properly.

We have seen large investment in stainless steel to allow the capacity to process these record-breaking volumes. While disguised this way and that, the bottom line is the cow is paying for that also. We had little in the way of joined-up thinking on any investment in stainless steel so far and many executives justified it, saying it will all be needed.

Are we any further down the line for phase two of the investment? It would look unlikely.

We are beginning to hear justification from some executives that the cost of the additional stainless steel is one of the reasons Irish milk prices are behind international prices. Interestingly, when the funding was being sourced from farmers and banks, all the talk was about how this investment was going to add value.

Farmers sitting on co-op boards and farmers in general need to be very careful on the next wave of investment. All the figures suggest more milk is on the way from farms all over Ireland. It is fair to say not as many dairy farmers will be expanding and, inevitably, the debate will turn to who should fund the additional steel.

Should all farmers feel the pain – even those not expanding? Has the time come for a variation of investment per additional kilo of milk solids produced? Would that keep unnecessary spending to a minimum? Would that drive more joined-up thinking?

It’s better to have the debate now than wait for a €100m investment to lie idle in five or 10 years’ time.

From a farmer’s perspective, the timing of the EU-Mercosur deal couldn’t be worse. The announcement that the Mercosur bloc of South American countries has secured access for 99,000t of beef at a reduced tariff rate into the EU, plus a total elimination of tariffs on 47,000t Hilton quota, comes as farmers struggle to deal with a collapse in beef price across the EU.

There are two factors at play. First is a slump in demand for beef, reflecting the extent to which many consumers see eating less beef as a step towards doing their bit for climate change. Second is the ongoing market disruption being caused by the threat of a no-deal Brexit.

The move by the European Commission to put forward an agreement with Mercosur has generated real anger among EU beef farmers, and nowhere more so than in Ireland, where farmers feel this is another attempt to wind down the national suckler herd.

So does a Mercosur trade deal spell the end of the sucker cow? It certainly has the potential to but as Minister for Agriculture Michael Creed outlines, the political agreement announced last week has a lot of hurdles still to jump.

Our specialist team analyses the agreement and details the time lines this week. Ratifying the deal will be a slow process. European Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan indicates that it could be 2028 before it is operational – if approved. In this sense, the threat is more distant and should not distract from the challenge of Brexit. If Brexit goes wrong, we will not have to worry about of increased volumes of South American beef in 2028.

Despite some confusion, no EU member state can unilaterally veto the Mercosur deal.

As Phelim O’Neill, the proposed agreement must be ratified by both the Trade Policy Committee (TPC), made up of EU trade Ministers, and the European Parliament. Within the TPC, a qualified majority is required consisting of 55% of member states representing 65% of the population. Minister Creed has committed to frustrate the deal by trying to build a blocking alliance within the TPC. It will be difficult in the absence of French support.

The deal may well face a bigger hurdle in the European Parliament, which, in the wake of recent elections, now has a much greener tilt.

The failure to allocate a specific product quota within the tariff rate quota (TRQ) is a real concern. It allows the Mercosur bloc to cherry-pick steaking cuts into the EU

Given the obvious policy divergence in relation to environmental standards, it will be interesting to see if green MEPs are prepared to show their colours in preventing the Commission effectively moving to outsource their climate responsibilities.

Additionally, perhaps the biggest threat to the agreement reaching completion may be Mercosur itself. The coalition has always proved highly volatile with changes to the political leadership within the trading bloc having derailed previous negotiations.

Commissioner Hogan is unequivocal in that if climate commitments – particularly in relation to deforestation – are not implemented, then the deal will be scrapped. With Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro having traditionally leaned more towards Trump-like climate policies, the environmental conditions attached to the agreement will require a transformation in Brazil where deforestation is currently running at record levels.

Assuming all hurdles are jumped and a deal is ratified, Commissioner Hogan has left the EU with no wiggle room regarding standards. In a meeting with the Irish Farmers Journal, he stated that the South American countries will have to comply 100% with EU standards on farms supplying the EU market. This represents a significant change from the past, when Brazilian beef could enter the EU from farms where standards did not mirror those in the EU.

Given Brazil’s inability to meet equivalent standards and the EU’s failure to adequately monitor standards, the IFA is right to be suspicious of such commitments from Hogan.

The failure to allocate a specific product quota within the tariff rate quota (TRQ) is a real concern. It allows the Mercosur bloc to cherry-pick steaking cuts into the EU, allowing the potential to cause huge market disturbance. However, Commissioner Hogan argues that the introduction of a safeguard mechanism that allows for a two-year suspension of trade where evidence of market disruption can be identified provides the necessary protection.

Key to protecting the EU beef and poultry market in the event of any deal will be to ensure climate, production and welfare standards are enforced. Both farm organisations and MEPs should demand that before any deal can be ratified, an independent competent authority should be appointed to ensure that all measures contained within the agreement relating to standards, animal welfare and environmental controls are fully implemented, and that safeguards are triggered when required.

We should remember that in the past, when Brazil was forced to meet EU standards, the added costs saw their appetite to supply the EU dwindle.

There is no upside in the Mercosur agreement for the beef and poultry sectors. However, it doesn’t mean that it is time to shut the door on our suckler sector. Any deal will take up to a decade to come into full force so there is no need for immediate panic or to be distracted from more immediate Brexit issues.

Regardless of what happens in Mercosur, the need to develop a coherent strategy for our suckler herd is clear.

Hogan insists that tools are in place under the CAP to protect the financial viability of suckler beef production in Ireland. However, this will require Minister Creed and farm organisations to debate the thorny issue of top slicing payments to establish a fund to protect vulnerable sectors.

The willingness within the European Commission to establish a new REPS scheme and couple supports for sucker cows shows the scope that exists to provide financial support.

These supports must be in place well in advance of any Mercosur deal.

Moorepark open day: huge turnout reflective of a sector that is driving ahead

The turnout in Moorepark on Wednesday was testament to a sector that is driving ahead in more ways than one. The enthusiasm was palpable from dairy farmers who have been milking cows for over 30 years, other farmers considering milking cows and a large cross-section of the service industry.

Like any sector leaving a margin, the spin-off into rural Ireland is real and that’s what creates the buzz.

It all hinges on dairy farmers managing grass properly and using highly fertile genetics – the message has been consistent for a good number of years at similar days. There are of course challenges but none insurmountable once managed properly.

We have seen large investment in stainless steel to allow the capacity to process these record-breaking volumes. While disguised this way and that, the bottom line is the cow is paying for that also. We had little in the way of joined-up thinking on any investment in stainless steel so far and many executives justified it, saying it will all be needed.

Are we any further down the line for phase two of the investment? It would look unlikely.

We are beginning to hear justification from some executives that the cost of the additional stainless steel is one of the reasons Irish milk prices are behind international prices. Interestingly, when the funding was being sourced from farmers and banks, all the talk was about how this investment was going to add value.

Farmers sitting on co-op boards and farmers in general need to be very careful on the next wave of investment. All the figures suggest more milk is on the way from farms all over Ireland. It is fair to say not as many dairy farmers will be expanding and, inevitably, the debate will turn to who should fund the additional steel.

Should all farmers feel the pain – even those not expanding? Has the time come for a variation of investment per additional kilo of milk solids produced? Would that keep unnecessary spending to a minimum? Would that drive more joined-up thinking?

It’s better to have the debate now than wait for a €100m investment to lie idle in five or 10 years’ time.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: